Biblical Perspectives

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

Tuesday, October 1, 2019

week 2 bak

CHIASM

From the ridiculous:

- "I am stuck on Band Aid..

- "Never let a kiss fool you..

To the sublime:

- "Ask not what your country can do for you..

- "God is good all the time.."

- "When the going gets tough.."

- "Accept rejection.."

To the biblical:

- The first shall be last...

- Whoever humbles themself will be exalted...

- You do unto others...

Chiasm(definition) ).. once you are attuned to seeing them in Scripture (and most ancient literature) it seems they are everywhere.

Sometimes they are.

- "I am stuck on Band Aid..

- "Never let a kiss fool you..

- "Ask not what your country can do for you..

- "God is good all the time.."

- "When the going gets tough.."

- "Accept rejection.."

To the biblical:

- The first shall be last...

- Whoever humbles themself will be exalted...

- You do unto others...

Sometimes they are.

--

--

PHILEMON: there could be a helpful chiasm in Philemon..Further hint: check verse 5 in our class translation

PHILEMON: there could be a helpful chiasm in Philemon..Further hint: check verse 5 in our class translation

Thursday, September 12, 2019

Philemon help

|

Philemon help?

.Biblical Perspectives Signature (SIGNature) Assignment

(final paper)

Due: three days

after last class, by 11:59 p.m. Submit to Turnitin.com

TASK

The signature assignment (final paper) for Biblical Perspectives is designated as a significant 7-9 page paper that

is designed addresses the

meaning of a biblical text. Using the skills gained in the course, develop a

paper that combines an understanding of the historical, literary and

contemporary worlds of the text. The text for this assignment is the New Testament book of Philemon. (Don’t

resign the class until

you are done. Resignation often comes too soon).

PURPOSE

The paper is meant

to demonstrate the student’s own analysis and ability to work with a biblical

text and as such need not utilize other resources as in a traditional research

paper. This is a NOT a research paper;

it is a SEARCH paper, where you search out what you think is the

meaning/message of Philemon.

However, it could

be hugely helpful (and improve your grade) to draw in one (or perhaps more)

lessons from class to build your thesis.

FORM

Thesis: The paper should include a clear

thesis statement (somewhere in your

paper) in the form of “the book of

Philemon is about…” Note: by

“about,” we mean not just “about” in the sense of storyline and

characters—though you definitely include that somewhere in your paper, as

well. We mean

what the book is ultimately “about”—life lesson, message, moral, sermon point

or Contemporary World “app.” Make it general;

do not include characters from the story in your statement. Be as specific and

concise as possible.

Body: The body of the paper should

demonstrate a recognizable structure that articulates why the thesis is viable.

The body of the paper may take the form of a verse by verse analysis, follow

the categories of historical/literary/contemporary worlds, or use any thematic

analysis that is most useful.

Conclusion: The conclusion should restate the thesis and

the support in summary fashion. The conclusion is also a place for reflection

on the implications of Philemon for your life and work. Apply it to your daily

life/work.

Sign (Symbol): Throughout this course we have been

using one guiding sign for each night, corresponding to the theme of the

evening. Based on your study of the book

of Philemon, develop your own sign/symbol that you feel adequately conveys the message

of the book and explain it in a paragraph.

Papers will not be accepted without the sign and explanation. (The sign is something you draw or create,

not anything you find online or elsewhere)

Be sure to also

include: Evidence from the text re: whether the slavery (of Onesimus) and

brotherhood of Philemon and Onesimus are literal, metaphorical, or both. Evidence

from the text re: whether Onesimus ran away.

GRADING:

Grading is based

upon how well the thesis is stated and supported, by the clarity of the

structure, by the depth of thought and by the quality of mechanics (spelling,

grammar).

See the meaning of

letter grades at FPU below.

All papers must be submitted to turnitin.com (instructions on next

page).

If there are red

marks in every paragraph for grammar/spelling/mechanics, the paper will not

pass. Big rules: no “you”/”your” words/language or contractions

From FPU HANDBOOK:

A=Superior. The student has demonstrated a quality of work and accomplishment far beyond the formal requirements and shown originality of thought and mastery of material.

B=Above Average.

The student’s achievement exceeds the usual accomplishment, showing a clear

indication of initiative and grasp of subject.

C=Average. The student has met the formal requirements and has demonstrated good comprehension of the subject and reasonable ability to handle ideas.

D=Below Average. The student’s accomplishment leaves much to be desired. Minimum requirements have been met but were inadequate.

Don't make any claims or assertions without evidence from the text of Philemon itself.

Especially regarding slavery etc

.

PHILEMON HELP? It would help to start collecting notes for your final paper on Philemon as soon as possible, as in a sense the whole class is preparing you to apply your "Three Worlds" skills to it. I would start by reading it over (click here to read it in a few different translations) and listening to it a few times (audio below) and then going through the Three Worlds questions in syllabus.

Take a look at the "HOW TO STUDY A TEXT VIA THREE WORLDS" tab on our website, and consider using it as the lens for studying and writing your paper

Come up with a working written definition of what the book seems to be about. Then you might want to branch out and watch some of the videos and commentaries linked below, remembering that they may not all get it "right," (and that includes N.T, Wright, if you pardon the pun) and you will see some things that the "experts" don't. The commentaries will be helpful in understanding "historical world" background. Pay careful attention to the instructions on the syllabus. You do not have to cite any sources, but if you do, be sure you attribute them in your paper.

See first two minutes of this video from an an online version of class:

/

If, for your paper, you want to consider CHIASMin Philemon, after searching out any such structures yourselves (which you are getting good at!), consider:

'

" I hear about your

It's a chiasm because Love and Faith are attributes, thus a pair, and Jesus and saints are persons. We know "faith" connects to Jesus in the Bible, never people.

==Literary World structure/sentence diagram.. Class translation with verse 5 restored to original order

love and faith

towards Lord Jesus and all the saints "

ABAB is a parallelism, not reversed, so not a chiasm.

ABBA is a reverse parallelism, this chiasm.

It's a chiasm because Love and Faith are attributes, thus a pair, and Jesus and saints are persons. We know "faith" connects to Jesus in the Bible, never people.towards Lord Jesus and all the saints "

ABAB is a parallelism, not reversed, so not a chiasm.

ABBA is a reverse parallelism, this chiasm.

==Literary World structure/sentence diagram.. Class translation with verse 5 restored to original order

PHILEMON:

Paul, a prisoner of Christ Jesus,

and Timothy our brother,

To Philemon our dear friend and fellow worker

also to Apphia our sister and

Archippus our fellow soldier

—and to the church

that meets in your home:

3 Grace and peace

to you (plural)

from God our Father

and the Lord Jesus Christ.

4 I always thank my God as I remember you in my prayers,

5 because I hear about your

love and faith

towards Lord Jesus and all the saints

6 I pray that your partnership with us in the faith may be effective

in deepening your understanding of every good thing we share for the sake of Christ.

7 Your love has given me great joy

and encouragement,

because you, brother, have refreshed the hearts of the saints.

towards Lord Jesus and all the saints

8 Therefore

although in Christ I could be bold, and order you to do what you ought to do,

9 yet I prefer to appeal to you on the basis of love.

It is as none other than Paul— an old man (elder)

and now also a prisoner of Christ Jesus—

10 that I appeal to you for my son--

Onesimus,["Useful"]"

who became my son while I was in chains.

11 Formerly he was useless to you,

but now he has become useful both to you and to me.

12 I am sending him

—who is my very heart

—back to you.

13 I would have liked to keep him with me

so that

he could take

your place

in helping me

while I am in chains for the gospel.

14 But I did not want to do anything without your consent,

so that any favor you do would not seem forced

but would be voluntary.

15 Perhaps the reason he was separated from you for a little while

was that you might have him back forever—

16 no longer as a slave,

but more than a slave,

as a dear brother.

He is that to me,

but even more so to you,

both in the flesh

and in the Lord.

17 So..

if you consider me a partner,

welcome him

as you would welcome me.

18 If he has done you any wrong or owes you anything,

charge it to me.

19 I, Paul, am writing this with my own hand:

I will pay it back!

(not to mention that you owe me your very self)

20 I do wish, brother, that I may have some benefit or usefulness from you in the Lord;

refresh my heart in Christ.

21 Confident of your obedience,

I write to you,

knowing that you will do even more than I ask.

22 And one thing more:

Prepare a guest room for me,

because I hope to be restored to you (plural)

in answer to your (plural) prayers.

23 Epaphras,

my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus,

sends you greetings.

24 And so do Mark,

Aristarchus,

Demas

and Luke,

my fellow workers.

25 The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ be with your (plural) spirit.

See also:

Also,consider a large chiasm in the book. If that's the case, the thesis is in the middle/midpoint:

- PHILEMON AS CHIASM WITH VERSE 14 AS CENTER

- THE SAME CHIASM AS ABOVE, WITH MORE DETAIL

- SAME CHIASM , SEEN A BIT DIFFERENTLY

- SAME CHIASM, DIFFERENTLY AGAIN

- -----------------------------------------

- INTERESTING INCLUSIO AND CHIASM OF NAMES IN PHILEMON

------------------------------------

Great help from Brian Dodd here

25 The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ be with your (plural) spirit.

See also:

Also,consider a large chiasm in the book. If that's the case, the thesis is in the middle/midpoint:

- PHILEMON AS CHIASM WITH VERSE 14 AS CENTER

- THE SAME CHIASM AS ABOVE, WITH MORE DETAIL

- SAME CHIASM , SEEN A BIT DIFFERENTLY

- SAME CHIASM, DIFFERENTLY AGAIN

- -----------------------------------------

- INTERESTING INCLUSIO AND CHIASM OF NAMES IN PHILEMON

------------------------------------

==

00000000000000000000000000000000

-----Breaking news. FREE online course on Philemon by NT WRIGHT>

Preview below and click here to check it out

>>>N.T. Wright's sermon (below, we watched in class)will be helpful, as are his comments about the letter here, and his study questions on pages 55-57 here).

Newer video: Wright in the "Time Bomb" of Philemon against slavery:

Here's a "word cloud" representation of word frequency in Philemon. What do you notice?:

(all New Testament word clouds here)

S

---Re-Read Philemon from you class Bible, or just click here. to read it online.

Now Read the short article on possible allegory here in Philemon come back here to post a few sentences response.

BTW, Henri Nouwen, author of the "In the Name of Jesus" book you read, wrote a famous book about the Prodigal Son (read about it here if you are interested) based on seeing this Rembrandt painting of The Prodigal Son story

BTW, Henri Nouwen, author of the "In the Name of Jesus" book you read, wrote a famous book about the Prodigal Son (read about it here if you are interested) based on seeing this Rembrandt painting of The Prodigal Son story

part c) Re-read the opening (verses 1-2 )and closing (verses 24-25) of Philemon here . Now Read Colossians chapter 4 at this link This is another letter from the Bible that seems to be written at the same time as Philemon. Note red sections.. What do you notice, and how might this help you interpret Philemon? Finally, consider this.

--

DDOUBLE DARE : Prodigal Son and Onesimus

BTW, Henri Nouwen, author of the "In the Name of Jesus" book you read, wrote a famous book about the Prodigal Son (read about it here if you are interested) based on seeing this Rembrandt painting of The Prodigal Son story

BTW, Henri Nouwen, author of the "In the Name of Jesus" book you read, wrote a famous book about the Prodigal Son (read about it here if you are interested) based on seeing this Rembrandt painting of The Prodigal Son story

a)Read the parable of the Prodigal Son here Then close your Bible, and retell the story to yourself...or better...someone else, summarizing, paraphrasing, and including important shifts.

THEN and only then, read this (or same info pages 14-17 here .) Think about whether or not in your retelling, you did what most North Americans do in their retelling, and if not, what that might mean from a Three Worlds perspective.

b) Listen to the first five minutes, or a random five minutes of the middle or end of this podcast by NT Wright on :Prodigal Son., . Post a sentence about any learnings. Of course, it is recommended you watch the whole thing as it's loaded with Three Worlds insights but I will make that optional due to it being a half hour . You decided after watching your five minutes of you want to watch it all. Be sure to include in your post which five minutes (beginning, middle or end) you chose and why

c)Here are some resources on the Prodigal Son as an eastern/Asian parable to scan. By Ray Van Der Laan and others (5 min) on the Prodigal Son.

d)Now read Philemon, thinking: How might The Prodigal Son story connect to Philemon and Onesimus? (This may help...or this if you are stuck.

------------------------------

Scot McKnight is a good resource:

"The Challenge to Philemon"

Video questions:

1)Notice that...like last time, he opens with a story that he promises to return to at the end This is INCLUSIO again.. Before you hear the end, guess why he tells this story. Guess how it will end.

2)What does he say is the best and hardest thing about the gospel?

3)Again, he mentions a word several times in the first few minutes that might be his thesis for our Philemon paper.

What is the word? Did you catch it last time? Agree/disagree that this may be the key word?

4)"Paul probably loves ______... He created enough of it."

5)Apply Keith Brock's definition of slavery to something in our contemporary world. What is it also true of in our day?

6)The family life of a slave depended on ____

7)What is the most "dramatic...unbelievable....glorious" part of the letter and why?

8)Why does he think Paul used "perhaps"? Compare this to your answer to this yours (see your Literary World worksheet from week 3

9)At the end of the video, how does he end the story he started at the beginning? Respond to this story.

"The Challenge to Philemon" - Dr. Scot McKnight from B.L. Fisher Library on Vimeo.

------------------

What's Philemon about?:

--

Philemon:"full of inside jokes.. the most fun anyone ever had writing while incarcerated..Paul's most absurd paradoxes"

Sarah Ruden, in Paul Among the People (Amazon here;

Christianity Today article and interview here) spends some time in the preface; as well as most of Chapter 6, on Philemon. A worthy read! (Sorry about the formatting below, click the links for a cleaner read; see also Philemon: full of humor?

and THESES ON PHILEMON: REDUCTION OF SEDUCTION)

From the preface:

--Christianity Today article and interview here) spends some time in the preface; as well as most of Chapter 6, on Philemon. A worthy read! (Sorry about the formatting below, click the links for a cleaner read; see also Philemon: full of humor?

and THESES ON PHILEMON: REDUCTION OF SEDUCTION)

From the preface:

The letter to Philemon...is full of inside jokes and high-as-a-kite invocations of the transcendent...Paul joyfully mocks the notion that any person placing himself in the hands of God can be limited or degraded in any way that matters. The letter must represent the most fun anyone ever had writing while incarcerated.From Chapter 6:

The letter to Philemon may the most explicit demonstration of how, more than anyone else, Paul created the western individual human being, unconditionally precious to God and therefore entitled to the consideration of other human beings. -page xix, preface, read the whole preface here

But bare forgiveness was radical enough, especially in the main territory of Paul's mission

But bare forgiveness was radical enough, especially in themain territory of Paul’s mission. There, forgiving a runawayslave (particularly a runaway who had taken goods with him,as Onesimus may have done), instead of sending him to hardlabor, branding him, crucifying him, or whipping him todeath, was no small matter, when he had so shockinglybetrayed his household (familia in Latin, from which we havethe obvious derivative). Running away and its punishmentsare the stuff of black comedy. The ancients treated suchepisodes almost the way we treat sex acts: the details are tooshameful for mainstream literature or polite conversation.For the Romans as for us, a single-word insult—for them“runaway”—could invoke adequate disgust on its own.

To show the extremity of what Paul faced in having a run-away slave land in his lap, I will start with a scene inPetronius. Imagine what the apostle got used to in the estab-lished Greco-Roman society he experienced, as when he wasstaying with a man wealthy enough to have a guest room, asPhilemon did. Petronius’s story of Trimalchio’s dinner partyis exaggerated and absurd, but the narrator Encolpius pro-vides the voice of cultured common sense among all of thepretentious uproar. From him we know that it was good formfor the master to order severe punishment for slaves even inthe case of carelessness and accidents that in any way marred

hospitality. It was also apparently polite for the guests tointervene, in the spirit of “Oh, no, not on my behalf, please!"..

...To be seen and never heard was not the universal rule.

Some slaves gained status in households and entered intoclose relationships with their masters. Cicero’s secretary Tirois an example. Some masters, like Seneca, vaunted theirhumanity toward slaves. But I submit that slaves were likepets: good treatment of them was about the masters’ enlight-enment, never about the slaves’ inherent equality. The mas-ter was absolutely entitled to keep a slave in line, accordingto his own convenience.

....The most subhuman slave was the runaway; his only tiesto society had been the uses that real people could make ofhim, and he now forfeited these ties. He was a little like araped or adulterous woman, but unlike her he bore all of theloathing and fury, in this case the extreme loathing and furythat come when absolute privilege is disappointed.

As a rule, a runaway was simply a lost cause: a far-out out-law as long as he could sustain it, and a tortured animal or a

carcass when caught. Here is a rare detailed depiction. InPetronius, characters masquerade as caught runaways afterthey realize they have a choice between being recognized andkilled, and becoming objects whose repulsiveness will barany other impression from onlookers’ minds. They shavetheir heads as part of the disguise, and even after this act hasbeen reported to the owner of the ship on which they are sail-ing—haircutting at sea was considered a bad omen—andthey must stand in the middle of an angry crowd thatincludes their longtime enemies, their protector still hopesthat their role of degradation will shield their identity..

...Again, who a runaway was—nobody and nothing—tells

us who a slave was: nobody and nothing aside from his use-fulness. And Aristotle and others indicate that he is inher-ently that. This is what makes the debate over the letter toPhilemon, concentrating on the question of legal freedom, sosilly. We are not in the ancient Near East, where the peoplewho were slaves in Egypt become masters in Canaan. Such achange was not conceivable in the polytheistic RomanEmpire. Had Philemon freed Onesimus, it would not haveturned Onesimus into a full human being. That is what Paulwants, so he does not ask for the tool that won’t achieve it..

....But as I wrote above, Paul had a much more ambitiousplan than making Onesimus legally free. He wanted to makehim into a human being, and he had a paradigm. As Godchose and loved and guided the Israelites, he had now chosenand loved and could guide everyone. The grace of God couldmake what was subhuman into what was more than human.It was just a question of knowing it and letting it happen.The way Paul makes the point in his letter to Philemon isbeyond ingenious. He equates Onesimus with a son and abrother. He turns what Greco-Roman society saw as the fun-damental, insurmountable differences between a slave andhis master into an immense joke.

This chapter and previous ones have given some idea ofwho the most and the least replaceable people were in theeyes of the Greeks and Romans. I just want to stress againhow crucial the relationship was between freeborn fathersand their legitimate sons, and between full freeborn brothers.Along with the misconstruing of ancient slavery, a huge bar-rier to modern readers’ getting Philemon is that we can’t,just from our own experience, see fatherhood and brother-hood as sacred—they have not been so for hundreds of years..

...Brothers also played important roles in the Greek andRoman social systems. They were supposed to have close bondsof trust and affection, which were idealized in myth and his-tory. The archetypal brothers were the gods Castor andPollux. In one version of their story, the immortal brotherrefuses to accept the death of the mortal one and extractsfrom Zeus permission to sacrifice part of his own godhead sothat the two can remain together: they now spend alternatedays on Olympus and in the underworld. In another ending,they become a constellation, the Twins, or Gemini.

In Roman thinking, the legendary first king Romulus’skilling of his brother, Remus, was almost like original sin, apresage of the heinous “fraternal slaughter” in the civil wars:Romans, people of the same blood, essentially of the sameclan, tragically echoed Romulus’s crime.

Since there was no rule of primogeniture (by which theeldest son gets most or all of the inheritance) among eitherthe Greeks or the Romans, brothers were on a fairly equalfooting and were expected to collaborate constantly for thegood of the family. “Brother” could be a metaphor for otherclose and equal relationships, but Greeks and Romans neverused the term to createa sense of closeness and equality out ofdivision. Christians did, which at the start would haveseemed bizarre. Imagine the impropriety of calling every-body at an open religious gathering “husbands and wives.” Infact, a rumor that did much damage to the early church wasthat the meetings of “brothers and sisters” involved incest.

A slave was a son of no one. No man could claim him as a child,and no slave could make a claim on any man as his father. Hecould never be sure who his full biological siblings were—not that, officially, it mattered. But Paul unites all of thesecategories in writing of Onesimus, in the most thoroughgo-ing, absurd set of paradoxes in all of his letters

Onesimus, though a slave, is Paul’s acknowledged son.

2.

12.Onesimus, though an adult, has just been born.3.Paul, though a prisoner, has begotten a son.4.Paul, though physically helpless, is full of joy andconfidence.5.Paul is ecstatic to have begotten a runaway slave.6.It is a sacrifice for Paul to send Onesimus back: he self-ishly wants the services of this runaway slave for him-self; conversely, he gives away his beloved newborn son.7.Paul has wanted Onesimus to remain with him in placeof Philemon, as if a runaway slave could be as muchuse to him, and in the same capacities, as the slave’smaster.8.Onesimus’s flight must result not in punishment but inpromotion to brotherhood with his master.9.Onesimus (“Profitable”) was perhaps unprofitable whentreated as a slave and certainly unprofitable as a run-away, but will be profitable when treated as a belovedbrother.10.Onesimus will be profitable not only to his master buteven to Paul.11.Onesimus, a runaway slave, must be treated as havingthe same value as Paul himself.nobody here but us bondsmen ·

Paul promises emphatically to pay any monetary dam-ages, but Philemon will (the reader senses) not takehim up on this.13.Philemon will acknowledge and act on all of this ofhis own free will, not needing any direct commandor explanation from Paul for this rather devastating-looking set of policies.14.Paul is confident that Philemon will do even morethan he asks, but what is he asking? For Philemon tomake Onesimus his brother in practical terms isimpossible; even if Philemon took the dizzying step ofmaking him an heir, he could not share with him hisown privileges as a freeborn person (assuming he isone)—laws forbid it. But even as a figure of speech oran ideal, what does “brother” mean? It is as if Paul werewriting, “I’m thinking of a big,bignumber. Guess what it is!”Paul may also be parodying letters of recommendation.*Such letters of Cicero have a similar fulsomeness, and a sim-ilar confident self-mockery as does the letter to Philemon. Acom mon come-on is along the lines of “I’m ridiculously excitedabout this person, but of course you’ll indulge me because ofthe valuable relationship between ourselves.” Cicero, likePaul, takes the whole responsibility and promises wonderfulbenefits. But Cicero’s letters of recommendation either askfor specific things or are about people who will ably figureout on their own what to do with a new connection. AndCicero always stresses the personal merits of the subject:*(He plays explicitly on the idea of “Letters of recommendation” in2Corinthians 3:1)

...Imagine, in this tradition, a prisoner writing on behalf ofa runaway slave and perhaps a thief, who may have no per-sonal merits whatsoever or may just now be starting to showsome, and who could not normally find hope in anything butpleas for mercy on his behalf from a man of material powerand influence with whom he has taken shelter. “Comic inver-sion” just doesn’t cover what is going on in this letter. Inworldly terms, it is like a janitor throwing a party for his dogand inviting a federal judge.

The solution, the punch line of the joke that is the letterto Philemon, the climax of this farce, is God. God alone hasthe power to make a runaway slave a son and brother, and infact to make any mess work out for the good—not that any-one knows how, but it doesn’t matter. Philemon has only tosurrender to the grace, peace, love, and faith the letter urges,and the miracle will happen. Paul seems to insist that it ishappening even as he prays for it, and he is goofy with joy:Philemon cannot say no to him, because God cannot say no.

-pp. 164-167, whole chapter on PDF here

Three readings of the letter:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

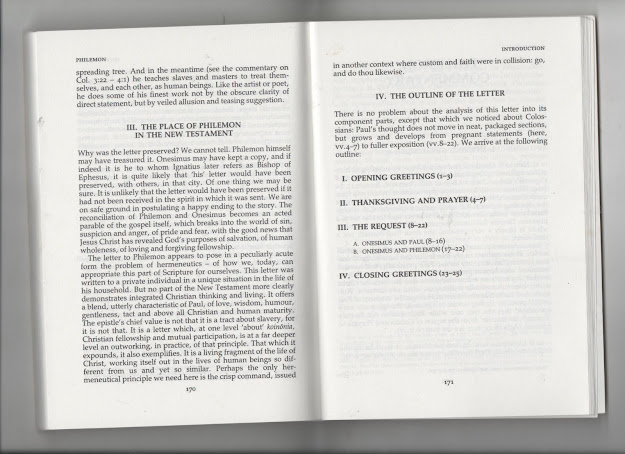

>>Here is a simple and helpful online commentary on Philemon

>>Here is an excellent one from IVP

>>several advanced online ARTICLES AND COMMENTARIES

Click a page to enlarge and read. Once you have a page open, you can click to magnify it.

-------------------

Kurt Willems, an FPU seminary student, has posted a helpful 5 part series on Philemon ( audio here):

Kurt Willems, an FPU seminary student, has posted a helpful 5 part series on Philemon ( audio here): Click:

Philemon, Forgiveness That Leads to Radical Reconciliation

-------James Dennison:

Perhaps we should approach Philemon by first analyzing its structure. You will observe that the first three verses include the names of five persons: Paul, Timothy, Philemon, Apphia, Archippus. You will further observe that the last three verses (vv. 23-25) conclude with the names of five persons: Epaphras, Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, Luke. Now observe also that the pattern of verses 1-3 is five names plus the phrase "the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ." This is precisely mirrored in verses 23-25: five names plus the phrase "the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ." The greeting or salutation of the epistle ends with the Lord Jesus Christ. The closing or conclusion of the epistle ends with the Lord Jesus Christ. A perfectly balanced inclusio structurally envelops the tender plea of the apostle on behalf of Onesimus. Paul, Timothy, Philemon, Apphia, Archippus—members of the church; Epaphras, Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, Luke—members of the church. Within the church, something new is occurring! LINK

Alternative views:

a)He might be a slave, but not a runaway. He simply was asking Paul for help in being an advocate. This view solves several problems with the traditional view, and this article is helpful on Paul's style of persuasion/theme of the letter. by Brian Dodd: click here

b)"This is not about a runaway slave at all. Paul and Onesimus are literal brothers.":

There are several problems with the interpretation that Onesimus is a runaway fugitive slave. There are other examples of letters written in the period that Paul was writing that implore slaves to return to their masters and that implore masters to receive their slaves back graciously. Paul’s letter to Philemon does not follow the same pattern.

In addition, the epistle itself never says that Onesimus is a runaway or a thief, this is simply a presumption. Finally, the entire argument that Onesimus is a slave is based on verse 15 and 16 where Paul uses the greek word doulos to describe Onesimus. Certainly the word can be interpreted as slave, however, the word is used many other times in scripture and does not always mean that the one called doulos is a literal slave. Sometimes doulos refers to a son or a wife, not a slave. That one word is not a definitive identification of Onesimus.

What if Callahan’s interpretation is correct? Onesimus not just a Christian, he is actually a blood brother to Philemon. This interpretation means that the book of Philemon is about reconciliation in families rather than an admonition for the slave to remain obedient and the master to treat the slave fairly. LINK: Philemon...Slave Master?

..and then we encounter these verses which have caused many varied interpretations. Verses 15-16. Callahan translates them as, “For on this account he has left for the moment, so that you might have him back forever, no longer as though he were a slave, but, more than a slave, as a beloved brother very much so to me, but now much more so to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord.”[1]NOTE also: metaphorical terminology by Paul re: slavery in Galatians 4:7:

First, there is a grammatical question about how to translate this phrase which many have rendered “no longer as a slave.” Callahan dissects the Greek and he argues that the phrase is more accurately translated, “no longer as though he were a slave.” Even with Callahan’s translation, the question remains: Why did Paul choose to use the word slave if Onesimus wasn’t a slave?

The word used is doulos and according to Callahan’s research, it “was a term of both honor and opprobrium in the early Christian lexicon.”[2]

It was thought to be an honor to be called a doulos tou theou or a slave of God. In fact, Paul calls himself a slave of Christ in several of his letters including Romans, Philippians, and Titus, as do other authors of the epistles of James and 2 Peter.

It is also true that the term slave signified subjugation, powerlessness, and dishonor, one who does not have liberty or agency on one’s own.

Callahan argues that Paul is using the term doulos to capture both dimensions of the human condition and is perhaps even making a connection with the Christ hymn in Philippians 2 where he quotes an ancient hymn that exalts the Christ who humbles himself to be nothing, powerless, and empty of the divine dimension, like a slave to the human condition.

Callahan argues that Paul is simply calling Onesimus a slave in the same way that he describes himself as a slave. Onesimus is also a doulos tou theou, a slave of God.

If this is the case, then Paul uses language that indicates Onesimus and Philemon are related, in fact that they are brothers in the flesh. Reconciliation and love between brothers was a special concern for several ancient writers and philosophers. One Roman philosopher named Plutarch writes of the importance of repairing a breach between brothers, even if it comes through a mutual friend...

-LINK: Philemon...Brother?

"So you are no longer a slave, but God’s child; and since you are his child, God has made you also an heir"... actually a verse quite similar to Philemon 16 (first clause the same, second clause family language)

"no longer as a slave, but better than a slave, as a dear brother."

OR MAYBE THE TWO ARE LITERAL BROTHERS AND ONESIMUS IS A SLAVE

See:

Philemon and Onesimus as (half) bothers AND slave/master

c) Philemon isn't the slaveowner at all, it is Archippus. Note: see this note in your class Bible..

Note that grammatically, the letter we call Philemon might be addressed not to the first mentioned (Philemon), but the last-mentioned (Archippus). Verse 1, 2:

To Philemon our dear friend and co-worker, to Apphia our sister,] to Archippus our fellow soldier, and to the church in your house..

See Colossians 4. Note same writer (Paul) and many similar names as the "Philemon" letter. What is the task Paul wants Archippus to fulfill? Could it be to release Onesimus?

Colossians 4.7 Tychicus will tell you all the news about me; he is a beloved brother, a faithful minister, and a fellow servant[b] in the Lord. 8 I have sent him to you for this very purpose, so that you may know how we are[c] and that he may encourage your hearts; 9 he is

coming with Onesimus, the faithful and beloved brother, who is one of you. They will tell you about everything here.

10 Aristarchus my fellow prisoner greets you, as does Mark the cousin of Barnabas, concerning whom you have received instructions—if he comes to you, welcome him. 11 And Jesus who is called Justus greets you. These are the only ones of the circumcision among my co-workers for the kingdom of God, and they have been a comfort to me. 12 Epaphras, who is one of you, a servant[d] of Christ Jesus, greets you. He is always wrestling in his prayers on your behalf, so that you may stand mature and fully assured in everything that God wills. 13 For I testify for him that he has worked hard for you and for those in Laodicea and in Hierapolis. 14 Luke, the beloved physician, and Demas greet you. 15 Give my greetings to the brothers and sisters[e] in Laodicea, and to Nympha and the church in her house. 16 And when this letter has been read among you, have it read also in the church of the Laodiceans; and see that you read also the letter from Laodicea. 17 And say to Archippus, “See that you

complete the task that you have received in the Lord.”

18 I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand. Remember my chains. Grace be with you.[f]

-----------------------------d)Allegory:

Philemon, an allegory?

Consider the following passage (Philemon 8-18) with these analogies in mind:

- Paul (the advocate) : Jesus

- Onesmus (the guilty slave) : us (sinners)

- Philemon (the slave owner) : God the Father

Martin Luther: "Even as Christ did for us with God the Father,

thus also St. Paul does for Onesimus with Philemon"

Accordingly, though I (Paul) am bold enough in Christ to command you (Philemon) to do what is required, yet for love's sake I prefer to appeal to you—I, Paul, an old man and now a prisoner also for Christ Jesus— I appeal to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I became in my imprisonment. (Formerly he was useless to you, but now he is indeed useful to you and to me.) I am sending him back to you, sending my very heart. I would have been glad to keep him with me, in order that he might serve me on your behalf during my imprisonment for the gospel, but I preferred to do nothing without your consent in order that your goodness might not be by compulsion but of your own free will. For this perhaps is why he was parted from you for a while, that you might have him back forever, no longer as a slave but more than a slave, as a beloved brother—especially to me, but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord.

So if you consider me your partner, receive him as you would receive me. If he has wronged you at all, or owes you anything, charge that to my account. I, Paul, write this with my own hand: I will repay it—to say nothing of your owing me even your own self. LINK: Philemon, an allegory?

-

THE SILENCE OF THE NEW TESTAMENT WRITERS ON SLAVERY

Though critics claim New Testament writers keep quiet about slavery, we see a subtle opposition to it in various ways. We can confidently say that Paul would have considered antebellum slavery with its slave trade to be an abomination — an utter violation of human dignity and an act of human theft. In Paul’s vice list in 1 Timothy 1:9,10, he expounds on the fifth through the ninth commandments (Exodus 20; Deuteronomy 5). There Paul condemns “slave traders” who steal what is not rightfully theirs.4

Critics wonder why Paul or New Testament writers (cp. 1 Peter 2:18–20) did not condemn slavery and tell masters to release their slaves. We need to first separate this question from other considerations. New Testament writers’ position on the negative status of slavery was clear on various points: (a) they repudiated slave trading; (b) they affirmed the full human dignity and equal spiritual status of slaves; (c) they encouraged slaves to acquire their freedom whenever possible (1 Corinthians 7:20–22); (d) their revolutionary Christian affirmations, if taken seriously, would help tear apart the fabric of the institution of slavery, which is what took full effect several centuries later — in the eventual eradication of slavery in Europe; and (e) in Revelation 18:11–13, doomed Babylon (the world of God-opposers) stands condemned because she had treated humans as “cargo,” having trafficked in “slaves [literally ‘bodies’] and human lives” (verse 13, NASB). This repudiation of treating humans as cargo assumes the doctrine of the image of God in all human beings.

Paul, along with Peter, did not call for an uprising to overthrow slavery in Rome. On the one hand, they did not want people to perceive the Christian faith as opposed to social order and harmony. Hence, New Testament writers told Christian slaves to do what is right. Even if they were mistreated, their conscience would be clear (1 Peter 2:18–20). Yes, obligations fell to these slaves without their prior agreement. So the path for early Christians to take was tricky — very much unlike the situation of voluntary servitude in Mosaic Law.

A slave uprising would do the gospel a disservice — and prove a direct threat to an oppressive Roman establishment (e.g., “Masters, release your slaves”; or, “Slaves, throw off your chains.”). Rome would quash flagrant opposition with speedy, lethal force. So Peter’s admonition to unjustly treated slaves implies a suffering endured without retaliation. Suffering in itself is not good; but the right response in the midst of suffering is commendable.

Early Christians undermined slavery indirectly, rejecting many common Greco-Roman assumptions about it (e.g., Aristotle’s) and acknowledging the intrinsic, equal worth of slaves. Since the New Testament leveled all distinctions at the foot of the cross, the Christian faith — being countercultural, revolutionary, and anti-status quo — was particularly attractive to slaves and lower classes. Thus, like yeast, Christlike living can have a gradual leavening effect on society so oppressive institutions such as slavery could finally fall away. This is, in fact, what took place throughout Europe: Slavery fizzled since “Christianized” Europeans clearly saw that owning another human being was contrary to creation and the new creation in Christ.5

President Abraham Lincoln, who despised slavery but approached it shrewdly, took this incremental strategy. Being an exceptional student of human nature, he recognized that political realities and predictable reactions to abolition required an incremental approach. The radical abolitionist route of John Brown and William Lloyd Garrison would (and did) simply create a social backlash against hard-core abolitionists and make emancipation more difficult.6

RETURNING ONESIMUS: A THROWBACK TO HAMMURABI?

Was Paul’s sending Onesimus back to his alleged owner Philemon a moral step backward? Was it more like the oppressive Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, which insisted on returning fugitive slaves to their masters — something prohibited in the Old Testament (Deuteronomy 23:15,16)? Some charge that Paul was siding with Hammurabi against the Old Testament.

Reading a New Testament epistle such as Philemon is like listening to only one party in a phone conversation. We only hear Paul’s voice, but plenty of gaps exist that we would like to have filled in. What was Paul’s relation to Philemon (“dear friend and fellow worker” and “partner” Philemon 1,17)? What debt did Philemon owe Paul? How had Onesimus wronged Philemon (if he even did)?7

Many interpreters have taken the liberty to help us fill in the gaps. The typical result? They read too much into the text. The common fugitive-slave hypothesis (that Onesimus was a runaway slave of Philemon’s) is quite late, dating back to the church father John Chrysostom (347–407 A.D.). However, genuine scholarly disagreement exists about this interpretation. For one thing, the epistle contains no “flight” verbs, as though Onesimus had suddenly gone AWOL. And Paul revealed no hint of fear that Philemon would brutally treat a returning Onesimus, as Roman masters typically did when they caught their runaway slaves.

Some have plausibly suggested that Onesimus and Philemon were estranged Christian (perhaps biological) brothers.8 Paul exhorted Philemon not to receive Onesimus as a slave (whose status in Roman society meant alienation and dishonor); rather he was to welcome Onesimus as a beloved brother: “that you might have him back for good —no longer as a slave, butbetter than a slave, as a dear brother. He is very dear to me but even dearer to you, both as a man and as a brother in the Lord” (Philemon 15,16, emphasis added).

Notice the similar sounding language in Galatians 4:7: “Therefore you are no longer a slave, but a son; and if a son, then an heir through God” (NASB, emphasis added). This may shed further light on how to interpret the epistle of Philemon. Paul wanted to help heal the rift so Philemon would receive Onesimus (not a slave) back as a beloved brother in the Lord — not even simply a biological brother. To do so would follow God’s own example in receiving us as sons and daughters rather than slaves.

Even if Onesimus were a slave, this still did not mean he was a fugitive. If a disagreement or misunderstanding had occurred between Onesimus and Philemon, and Onesimus had sought out Paul to intervene or arbitrate the dispute, this would not have rendered Onesimus an official fugitive. And given Paul’s knowledge of Philemon’s character and track record of Christian dedication, the suggestion that Onesimus’s coming back was Hammurabi revisited is off the mark. Again, if Onesimus were a slave in Onesimus’s household, Paul’s strategy was this: Instead of forbidding slavery, impose fellowship.9

In summary, Jesus and New Testament writers opposed oppression, slave trade, and treating humans as cargo. The earliest Christians were a revolutionary, new community united by Christ — a people transcending racial, social, and sexual barriers — which eventually led to a slavery-free Europe a few centuries later. link

--

When looking at "alternative" readings of Philemon, it is amazing how few even deal with the reality that the most obvious way to read vv 15-16-- "a dearly loved brother, both in the flesh and in the Lord" --as

When looking at "alternative" readings of Philemon, it is amazing how few even deal with the reality that the most obvious way to read vv 15-16-- "a dearly loved brother, both in the flesh and in the Lord" --as

both a literal and spiritual brother.

Tim Gombis is so right:

My main contention in these posts is that commentators must take Paul’s reference to Philemon and Onesimus as adelphoi en sarki with greater seriousness. It is highly unlikely that Paul regards the two as sharing in a common humanity. It is far more likely that they are actual brothers. This may demand a re-consideration of the scenario that eventuates in Paul’s letter, even though any modification to the consensus view need not be as dramatic as the view advanced by Callahan. link

Even N.T. Wright, who specializes in Philemon; even making it the key to his new magnum opus on Paul,

acknowledges the "literal brother" interpretation, but does not even consider it or discuss it (in 1700 pages) other than to say:

Just because Callahan may have gone too far, must we throw interpretations out with bathwater?

Is Wright (surely!) aware that they could be master/slave and literal brothers, as Gombid develops (here) and suggests "this is the most natural reading." Wright's work is indeed brilliant and seminal, but perhaps Moo has a point about him being too sure of his interpretations...to the degree that, though he is the nicest guy, he can seem dismissive:

Don't get me wrong, I'm still getting the T-shirt...just saying (:

Another post from Gombis:

I (Dave )have had similar experiences in college classes. Often in a class of fifteen, where most are reading the text for the first time, I ask "How many of you assumed Onesimus was a slave?" Often, no hands go up.

I need to ask : "How many of you assumed Onesimus was a Philemon's literal brother?"

Interesting that a far more popular (in the sense of "speaking to laypeople" and not in the academic journal world) writer than Wright, assumes the literal brother view, without even acknowledging the "traditional" view (emphases mine):

--

--

can Wright be wrong? Philemon and Onesimus as (half) bothers AND slave/master

When looking at "alternative" readings of Philemon, it is amazing how few even deal with the reality that the most obvious way to read vv 15-16-- "a dearly loved brother, both in the flesh and in the Lord" --as

When looking at "alternative" readings of Philemon, it is amazing how few even deal with the reality that the most obvious way to read vv 15-16-- "a dearly loved brother, both in the flesh and in the Lord" --asboth a literal and spiritual brother.

Tim Gombis is so right:

My main contention in these posts is that commentators must take Paul’s reference to Philemon and Onesimus as adelphoi en sarki with greater seriousness. It is highly unlikely that Paul regards the two as sharing in a common humanity. It is far more likely that they are actual brothers. This may demand a re-consideration of the scenario that eventuates in Paul’s letter, even though any modification to the consensus view need not be as dramatic as the view advanced by Callahan. link

Even N.T. Wright, who specializes in Philemon; even making it the key to his new magnum opus on Paul,

acknowledges the "literal brother" interpretation, but does not even consider it or discuss it (in 1700 pages) other than to say:

"one writer [Callahan] has even suggested that Philemon and Onesimus were not master and slave, but actual brothers who have fallen out, but, this too, has not found support." (p. 8)

Just because Callahan may have gone too far, must we throw interpretations out with bathwater?

Is Wright (surely!) aware that they could be master/slave and literal brothers, as Gombid develops (here) and suggests "this is the most natural reading." Wright's work is indeed brilliant and seminal, but perhaps Moo has a point about him being too sure of his interpretations...to the degree that, though he is the nicest guy, he can seem dismissive:

I won’t list other instances, but Paul and the Faithfulness of God contains too many of these kinds of rhetorically effective but exaggerated or overly generalized claims. A related problem is Wright’s tendency to set himself against the world—and then wonder why the world is so blind as to fail to see what he sees. A key thread, for instance, is Wright’s insistence that the basic story Paul’s working with has to do with God’s fulfillment of his covenant promises to Abraham—a vital focus that “almost all exegetes miss” and that has been “screened out from the official traditions of the church from at least the time of the great creeds” (494). This problem is sometimes compounded by a caricature of the tradition with which he disagrees Moo, full review

Don't get me wrong, I'm still getting the T-shirt...just saying (:

Another post from Gombis:

Several years ago I was teaching Bible study methods to undergrads and we were doing an exercise with the text of Paul’s letter to Philemon. A student raised his hand and noted that according to the text it appeared that Onesimus was the brother of Philemon.'

This sounded outrageous and obviously wrong, so I asked how he could possibly have arrived at that notion. He directed my attention to vv. 15-16. We were looking at the NASB:

For perhaps he was for this reason separated from you for a while, that you would have him back forever, no longer as a slave, but more than a slave, a beloved brother, especially to me, but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord.

I hadn’t studied this letter all that closely previously, so I assumed that Paul’s indication that they were brothers “both in the flesh and in the Lord” must mean something else. Other translations make this very assumption:

Perhaps the reason he was separated from you for a little while was that you might have him back forever—no longer as a slave, but better than a slave, as a dear brother. He is very dear to me but even dearer to you, both as a fellow man and as a brother in the Lord (NIV).

Maybe this is the reason that Onesimus was separated from you for a while so that you might have him back forever— 16 no longer as a slave but more than a slave—that is, as a dearly loved brother. He is especially a dearly loved brother to me. How much more can he become a brother to you, personally and spiritually in the Lord (CEB)!

I told him that I’d need to look at that a bit more closely and get back to him at a later point (one of those unfortunate classroom moments when you don’t have a ready answer–ugh!).

As I dipped into commentaries over the subsequent weeks and months, I was increasingly disappointed by how commentators treated Paul’s expression. The NIV’s and CEB’s renderings represent how nearly every major commentary I’ve looked at handles Paul’s expression...link

I (Dave )have had similar experiences in college classes. Often in a class of fifteen, where most are reading the text for the first time, I ask "How many of you assumed Onesimus was a slave?" Often, no hands go up.

I need to ask : "How many of you assumed Onesimus was a Philemon's literal brother?"

Interesting that a far more popular (in the sense of "speaking to laypeople" and not in the academic journal world) writer than Wright, assumes the literal brother view, without even acknowledging the "traditional" view (emphases mine):

Philemon is a marvelous example of the strongest force in the universe to affect control over someone -- grace. It takes up one of the most difficult problems we ever encounter, that of resolving quarrels between family members. We can ignore something a stranger does to hurt us, but it is very hard to forgive a member of our own family or someone close to us.

The key to this little letter is in the 16th verse. Paul says to Philemon that he is sending back Onesimus:

...no longer as a slave but more than a slave, as a beloved brother, especially to me but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord. (Philemon 1:16 RSV)

The background of this story is very interesting. This letter was written when the Apostle Paul was a prisoner in the city of Rome for the first time. It was sent to Philemon, a friend Paul had won to Christ, who lived in Colossae. Evidently Philemon had a young brother whose name was Onesimus.

Some way or another, we do not know how, Onesimus got into trouble -- maybe he was a gambling man -- and became the slave of his own brother, Philemon. In those days, if a man got into trouble, he could get somebody to redeem him by selling himself to that person as a slave. Perhaps Onesimus got into debt, and went to his brother, Philemon, and said, "Philemon, would you mind going to bat here for me? I'm in trouble and I need some money."

Philemon would say, "Well, Onesimus, what can you give me for security?"

Onesimus would say, "I haven't got a thing but myself, but I'll become your slave if you'll pay off this debt." Now that may or may not have been how it occurred, but the picture we get from this little letter is that Philemon is the brother of Onesimus, and his slave as well. -Ray Stedman, link

From FPU HANDBOOK:

A=Superior. The student has demonstrated a quality of work and accomplishment far beyond the formal requirements and shown originality of thought and mastery of material.

B=Above Average.

The student’s achievement exceeds the usual accomplishment, showing a clear

indication of initiative and grasp of subject.

C=Average. The student has met the formal requirements and has demonstrated good comprehension of the subject and reasonable ability to handle ideas.

D=Below Average. The student’s accomplishment leaves much to be desired. Minimum requirements have been met but were inadequate.

---

x

If Paul was in prison, and Onesimus came to him, where do you think he was?

Rome is 1,200 miles away , and would be a grueling journey on foot and by sea ( 1,200 miles on land, plus daring sea voyages which would themselves take 5-6 days)

Ephesus is about 100 miles away, a common walk in ancient world (3-4 days) .

--

Pliny vs. Paul

15JANby Chaplain Mike

N.T. Wright launches Paul and the Faithfulness of God in surprising fashion: by examining the NT story of Philemon in its context.

in surprising fashion: by examining the NT story of Philemon in its context.

He thinks that Philemon reveals that “something very different, different from the way the rest of the world behaved” was taking place through the early Christians. Wright suggests that this account is not just an example of extraordinary kindness, but rather represents something truly new in the world, something related to the message of Christos that is woven throughout the epistle.

Wright compares Philemon with a letter from a Roman senator named Pliny the Younger. Pliny wrote to a friend named Sabinianus about a freed slave who had angered him and had come to Pliny for help, fearing his former master’s wrath. Pliny, persuaded that the freedman was penitent, gave the refugee a stern lecture and then wrote to Sabinianus on his behalf.

The way Pliny reasoned with his friend reveals the social rules of the day. Pliny is in a power position, Sabinianus in the middle, and the freed slave at the bottom of the social pile. The freed slave needs and seeks out a friend in high places. The senator uses his position and attempts to convince his friend to take the penitent one back. Using a bit of ancient psychology, Pliny assures Sabinianus that he was right to be angry, but reminds him that anger might be counterproductive for his gentle personality. He lets him know that he has scolded and warned the offender and won’t give him another chance if he fails Sabinianus again.

The letter worked, and Sabinianus took the man back. As Wright notes, the freed slave was lucky that he could return and not face serious reprisals. In the end, the social order was restored, and the offender had received a strong enough lesson and warning that he dare not step out of line again. Sabinianus restored him on the basis of his repentance and the promise of better behavior, as well as a measure of self-interest in showing himself properly submissive to a superior.

How does this compare with Paul’s letter to Philemon about a situation regarding one Onesimus?

First of all, Wright notes a striking dissimilarity right at the start: Paul, the author, rather than holding a high position in society like Pliny, is in prison! Yet there is an air of strange authority in his words, as though being a prisoner were a noble calling.

But the main impression, once we study the two letters side by side, is that they breathe a different air. They are a world apart. Indeed — and this is part of the point of beginning the present book at this somewhat unlikely spot — this letter, the shortest of all Paul’s writings that we possess, gives us a clear sharp little window onto a phenomenon that demands a historical explanation, which in turn, as we shall see, demands a theological explanation. It is stretching the point only a little to suggest that, if we had no other first-century evidence for the movement that came to be called Christianity, this letter ought to make us think: Something is going on here. Something is different. People don’t say this sort of thing. This isn’t how the world works. A new way of life is being attempted — by no means entirely discontinuous with what was there already, but looking at things in a new way, trying out a new path.

– p. 6

N.T. Wright suggests that the story behind this letter is likely that which the majority of commentators have surmised: that Onesimus was a slave of Philemon who had run away. Wright thinks Paul was in prison in Ephesus at this time, which makes the slave’s journey from nearby Colossae to see him entirely plausible. There had been some sort of trouble between Onesimus and his master and he came to Paul to appeal for help in the situation.

N.T. Wright suggests that the story behind this letter is likely that which the majority of commentators have surmised: that Onesimus was a slave of Philemon who had run away. Wright thinks Paul was in prison in Ephesus at this time, which makes the slave’s journey from nearby Colossae to see him entirely plausible. There had been some sort of trouble between Onesimus and his master and he came to Paul to appeal for help in the situation.

Paul’s answer takes a much different tack than Pliny the Younger’s did in similar circumstances. Pliny’s counsel was, “The offender has said he’s sorry and you should take him back and give him another chance.” The senator’s intervention in this dispute did nothing to challenge the social conventions, rules, and roles of the day. It simply restored things to the status quo and kept all accepted identities and distinctions in place.

Wright discusses various parts of the letter and shows how Paul likely had certain Exodus themes in his mind as he appealed to Philemon, and how he uses different evocative terms of Christian fellowship to describe his relationships with both Philemon and Onesimus. But the nature of Paul’s appeal is most specifically highlighted in two important passages from the epistle that Wright analyzes.

- Paul’s prayer in v. 6 — Wright renders it: “that the partnership which goes with your faith may have its powerful effect, in realizing every good thing that is [at work] in us [to lead us] into the Messiah.” In particular, he wants us to see the final phrase: “into the Messiah.” Paul is praying that the dynamic gift of fellowship (koinonia) which accompanies Philemon’s faith will have the powerful effect of “bringing about Christos, Messiah-family, in Colossae.” As in Ephesians 4, where Paul envisions the church “growing up into Messiah,” so here he longs for the church in Colossae to know the full unity of life together in Christ.

- Paul’s request in v. 17 — “So, if you count me as your partner, receive him as you would me.” Philemon is not just to welcome Onesimus back as a penitent slave. He is to welcome him on the same level as if it were Paul himself! Furthermore, Paul offers to pay any damages the slave may have incurred: “If he has wronged you or owes you anything, put it down on my account.” Far from acting as a superior ordering an inferior to do something, Paul is willing to become personally, actively, even sacrificially involved to promote reconciliation.

N.T. Wright summarizes:

Here, too, is the most outstanding contrast between Pliny’s worldview and Paul’s. Paul is not only urging and requesting but actually embodying what he elsewhere calls “the ministry of reconciliation.” God was in the Messiah, reconciling the world to himself, he says in 2 Corinthians 5:19; now, we dare to say, God was in Paul reconciling Onesimus and Philemon.…The major difference between Pliny and Paul is that the heart of Paul’s argument is both a gently implicit Jewish story, the story of the exodus which we know from elsewhere to have been central in his thinking, and, still more importantly, the story of the Messiah who came to reconcile humans and God, Jews and gentiles and now slaves and masters. Paul’s worldview, and his theology, have been rethought around this centre. Hence the world of difference.

Pliny was concerned about resolving a problem in a way that maintained social order. Said social order was based on social distinctions and rules of propriety, as well as the rewards and punishments that kept it intact. Second chances were allowed up to a point; kindness and mercy had room to operate within limits. In the end, Pliny remained on top, Sabinianus was beholden to him, and the freedman was on the bottom of the pile.

Paul was concerned about two entirely different matters: reconciliation and unity in the Messiah. Paul was in prison because he advanced this agenda. From there he continued to promote these concerns to people like Philemon, by not only writing about them but also by offering to be the very bridge by which two parties at odds could become one again.

For Paul it was all about Jesus the Messiah, and this is what Jesus was all about. LINK

Pro:

' 1)Only letter of Paul not mentioning death of Jesus.. Why?

2)"extremely personal and never private"

3)Balance: we don't know what O did wrong or where Paul is in prison '

Con

1)Assumes he is slave and ran away..does it say that?

2)Assumes he is to be released from slavery..great idea, but evidence?

--

Christopher Scott was a student of mine who went to seminary, and his written on Philemon.

I've had him share in class. Here's a pic of me congratulating him as he was graduating FPU

See this for some of his Philemon articles on Philemon and leadership.

Warning: this class may lead to a lifelong love for Philemon,

--Student Katie Carson did a mind map of Philemon., Try it. Help here

----

--

Christopher Scott was a student of mine who went to seminary, and his written on Philemon.

I've had him share in class. Here's a pic of me congratulating him as he was graduating FPU

See this for some of his Philemon articles on Philemon and leadership.

Warning: this class may lead to a lifelong love for Philemon,

--Student Katie Carson did a mind map of Philemon., Try it. Help here

----

Who was Apphia?

This link suggests it was not Philemon's wife

Brian J. Dodd, at length:

Callahan, Allen Dwight. Embassy of Onesimus: The Letter of Paul to Philemon (Nt in Context Commentaries) . Bloomsbury: T and T Clark, 1997

Dodd , Brian J. Paul's Paradigmatic "I": Personal Example as Literary Strategy (Library of New Testament Studies) Sheffield: Sheffield Acadmic Press, 1999.

Pinnock, Sarah K., ed. The Theology of Dorothee Soelle. Harrisburg: Trinity Press, 2003.

=============================

This link suggests it was not Philemon's wife

APPHIA OF COLOSSAE: PHILEMON’S WIFE OR ANOTHER PHOEBE?

see also:

APPHIA

Scripture Reference—Philemon 1:2

Name Meaning—That which is fruitful

This believer, belonging to Colossae, the ancient Phrygian city now a part of Turkey, is spoken of as our “dearly beloved” and “our sister” (rv, margin). It is likely that she lived out the significance of her name by being a fruitful branch of the Vine. Apphia is believed to have been the wife of Philemon and either the mother or sister of Archippus who was evidently a close member of the family. She must have been closely associated with Philemon, otherwise she would not have been mentioned in connection with a domestic matter (Philemon 1:2). Tradition has it that Philemon, Apphia, Archippus and Onesimus were stoned to death during the reign of Nero. It was Onesimus who went to Colossae with a message for the Philemon household.

© 1988 Zondervan. All Rights Reserved

--

Click for

a helpful post:

chapter in

Onesimus Our Brother: Reading Religion, Race, and Culture in Philemon. Click:

"No Longer as a Slave”L Reading the Interpretation Histor yof Paul’s Epistle to PhilemonDemetrius K. William

by "illegally" welcoming Onesimus:

"...we find that Paul offered a biting critique of power and a creative path of revolutionary love. We might remember Paul urging his friend Philemon to illegally welcome back home a fugitive slave, Onesimus, as a brother, instead of killing him for running away. This is a scandalous subversion of Roman hierarchy. Paul was just as radical as Jesus. Remember that the Paul who "be subject to the authorities" is the same Paul who was stoned, exiled, jailed, and beaten for subverting the authorities... Is it possible to submit and to subvert? Paul's life gives a clear yes, as does Jesus' crucifixion" (Jesus For President, 161).

Paul's letter to Philemon was written to urge a former slave owner to illegally welcome back a fugitive slave (Onesimus)—a crime punishable by death—not as a slave but as a brother-Follow Me to Freedom, p. 134 (hear Ken and I interview Shane about this book here)

"...we find that Paul offered a biting critique of power and a creative path of revolutionary love. We might remember Paul urging his friend Philemon to illegally welcome back home a fugitive slave, Onesimus, as a brother, instead of killing him for running away. This is a scandalous subversion of Roman hierarchy. Paul was just as radical as Jesus. Remember that the Paul who "be subject to the authorities" is the same Paul who was stoned, exiled, jailed, and beaten for subverting the authorities... Is it possible to submit and to subvert? Paul's life gives a clear yes, as does Jesus' crucifixion" (Jesus For President, 161).

Paul's letter to Philemon was written to urge a former slave owner to illegally welcome back a fugitive slave (Onesimus)—a crime punishable by death—not as a slave but as a brother-Follow Me to Freedom, p. 134 (hear Ken and I interview Shane about this book here)

-------

THESES ON PHILEMON: REDUCTION OF SEDUCTION

-Dave Wainscott

"They carried the word ‘brotherhood’ always in the mouth, while they founded terror regimes."

- Hannah Arendt, Uber die Revolution, pp. 21; 318

PHILEMON REVISITED, PART ONE

THESES ON PHILEMON: REDUCTION OF SEDUCTION

“My theme is seduction, resistance, and the cultural consequences of both.”

That provocative opening line (p.1) of Henry Abelove’s monograph on John Wesley, The Evangelist of Desire, has always elicited from me a smile, as well as a healthy respect for its accurate prediction of the flow of his paper.

In a sense, Abelove’s salvo serves just as fittingly for the thematic intent of this current article, and in turn for the topic of the article itself: the biblical book of Philemon.

My working assumption is that Paul’s quietly subversive letter to Philemon--partly because its “theme is seduction, resistance, and the cultural consequences of both” --may well be the interpretive key and even kerygma-in-microcosm of the entire Pauline corpus, theology and worldview.

I do not view this claim as hyperbolic hubris; though I certainly concede that it is quite a supposition for a book that for most Christians is barely acknowledged and rarely read; and per many scholars is not sufficiently lengthy, meaty, or “theological’ (!) to merit such a distinguished and distinctive role in the canon.

If churchgoers have heard anything about this shortest letter of the New Testament, it is likely the “radio orthodoxy” (Brian McLaren’s delightful phrase) view that it is “about” Philemon’s runaway slave, and Paul’s encouragement that Philemon forgive said slave.

That party line may be partly right…and in the end, largely wrong.

If congregants have seriously studied the text beyond downloaded sermons and popular literature, they may have even run into Callahan’s alternative view (Callahan, 1997) that Philemon’s supposed slave Onesimus was not a slave at all, but literal brother to Philemon.

That take may be half-right; perhaps even dead wrong.

Philemon: Key and Keynote

Though it sounds counterintuitive to proffer that this tiny epistle holds the veritable key to all of Paul (among the more “obvious” candidates are the majestic narrative of Romans or the comprehensive compendium that is Ephesians), I am at least in good company: F.F. Bruce (1983), Marcus Bath (2000), and N.T. Wright (2013), to varying degrees and from differing angles, unashamedly assert the same.

Philemon : A Tale of Two Brothers

Though it may appear contrarian and contrary to accepted logic to offer that this letter is actually about a call for two brothers-by-blood to reconcile, there is no more obvious way to read verse 17 with grammatical and contextual integrity. Some (Callahan et al) are convinced that in Philemon, the slavery is metaphorical (not the brotherhood, as almost universally assumed), and the brotherhood is literal (not the slavery, as usually assumed). A surprisingly compelling case for this interpretation can be made; but more likely is the scenario that Philemon and Onesimus are both master/slave and brother/brother. Exegetes as astute as F.F .Bruce (not convinced) and Timothy Gombis (convinced) have weighed in here.

Philemon: Call to Manumission

Though it may feel a stretch for the historical milieu for Paul to be advocating release from slavery (manumission) for Onesimus, I make the case that Paul was prescient and prophetic enough to do just that…albeit between the lines… yet in a way clear and clamant for Philemon to decode and decide upon.

“Forgiveness, Radford Reuther suggests (in Pinnock, p, 205) “is not simply a transaction between God and the individual soul that has come to recognize its sinfulness. Politically interpreted, forgiveness means concrete acts of repentance expressed through social struggle to overcome oppression and to create a more just world.”

As for the “seduction, resistance, cultural consequences of both”?

Paul’s cruciform-shaped approach to leadership, status and power issues necessitates that any correspondence by him inevitably both incarnates (especially in a delightfully intentional choice of literary style and rhetorical genre) and advocates (via a surprisingly subtle-sneaky narrative arc) a radically Christocentric and stubbornly kenotic refusal to submit to the seduction of seeing a brother or sister in Christ (let alone sister or brother “in the flesh”) as “the other” or in any way less important than self. The cultural consequences--not just for ecclesiology, but for sociological issues such as slavery—are thus significant and sweeping. “History,” as Walter Wink would have it, “belongs to the intercessors.”

Bottom line, then? What is Philemon “about”?

Paul is writing to Philemon, about Philemon’s fugitive slave Onesimus, who is also Philemon’s half brother; he is arguing for unconditional restoration of Onesimus , which includes the “even more than I ask” release from slavery. This is all embedded with profound implications for subversion of empire and dismantling of ecclesiological hierarchy.

In this series of articles, we shall eventually weave all these theses into a tapestry and “contexture” with we believe is faithful to an informed hermeneutic. We begin with the initially confounding issue of Paul’s literary approach.

-----------------------------------------

THE LITERARY APPROACH OF PAUL: Humor, Holy Fool, Prosopeion, and ‘Paradigmatic I”

“I could command you, but I appeal to you ought of love”?

“Any decision you make will be spontaneous and not forced”?

“Oh, by the way, you owe me your would”

Paul’s language and literary approach have been much maligned, yet little understood. He has been read as being (at best) disingenuous and passive-aggressive, or (at worst) sycophantic and manipulative to a degree that borders on messianic complex. I believe a third way unpacks the dilemma and makes salient sense of the intuitive embarrassment and discomfort we feel overhearing Paul’s appeal. In a word: humor. In several words: a mosaic (and not at all prosaic) humor based loosely (?) on the “holy fool” tradition and rhetorical device of prosopeion; a holy humor laced liberally with a playful but profound twist of (almost) irony and mimetic self-reference. All of this is of course at great risk, and presupposes a deep, abiding and adamantine trust between sender and recipient.

Is Paul being authoritarian to a fault, all the while claiming the opposite? No, St. Paul is smarter…and not smarmier… than that. He is more humble than he has been given credit for; and decidedly not proud of his own humility. Per McLuhan, his medium masterfully matches—even equals and incarnates—his message.

On humor in Philemon, consider Marcus Barth:

In contrast to the doctrinal style of Romans; the irony and sarcasm found in Galatians; to the apologetic, wailing, and aggressive passages of Second Corinthians; and to other idiosyncrasies of other letters, in Philemon the use of contrasts is a sign and means of underlying good humor. Humor is, according to Wilhelm Busch, where one laughs, “in spite of it," even in the face of grave situations.

The mighty apostle of the omnipotent Lord Christ is a prisoner in Roman hands (w. 1, 9-10) and chooses the role of a beggar before Philemon (vv. 8-9). The child Onesimus was created by a father in chains (v. 10), who was, according to some versions of verse 9, an old man! A pun is made on the name Onesimus ("Useful") in verse 11. God's purpose in permitting separation was to establish eternal union (v. 15). Paul and Philemon are business partners, and Onesimus can substitute for Paul by being the third man in the association (v.17) Philemon is much deeper in debt to Paul than the apostle eventually is to the slave owner (vv 18-19). Paul hopes confidentially that he will benefit from Philemon — not only materially but by finding rest for his troubled heart (v 20)..... Overflowing obedience is the sum of complete voluntariness (v. 21.) A man whose chances for quick release from prison were less than certain invites himself to a private home for the near future (v. 22). All or at least a part of these elements can be considered, or are, humorous.

It is not certain whether Paul intended this impression, and whether Philemon was capable and willing to appreciate jokes pertaining to his relationship to Onesimus and to Paul. But together with other earliest hearers and readers of PHM, modern readers are by no means prevented from responding with a smile or a chuckle. The dreadfully serious issue of the slave Onesimus's future is treated lightly — a fact that reminds of the role of slaves in Greek and Latin comedies. Obviously bitterness is neither the only nor the best way of reacting to grave issues. Indeed, Philemon has a hard choice to make, but the decision-making process is sweetened as much as possible — by humor. (Barth and Blanke, 2000, pp. 118-19)

Paul is acting (literally) oddly, but not obsequiously. He is flirting with a not-quite full-blown prosopeion, a technique which is definitely in his repertoire and arsenal (see especially Romans 7); it is deployed here even more covertly than the infamous “I know a man..” of 2 Corinthians 13.